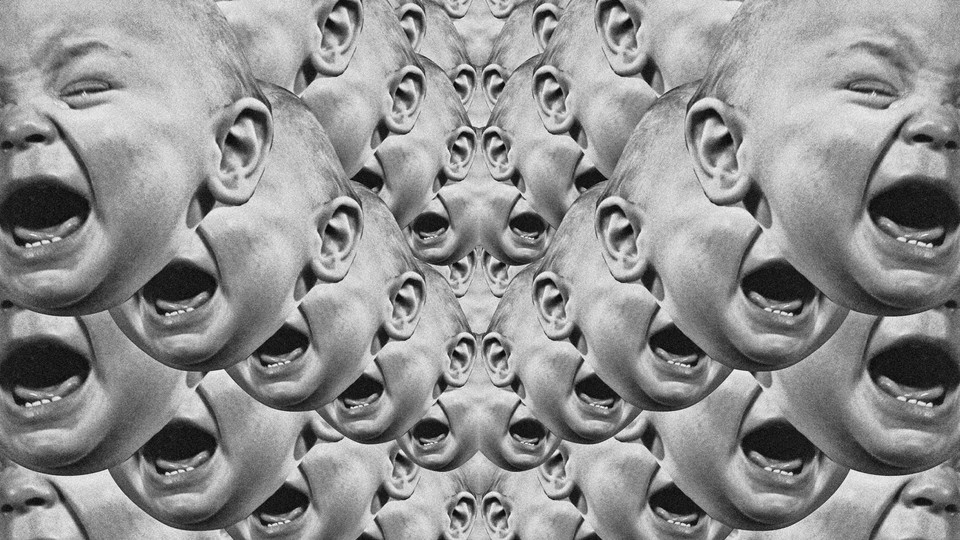

My 20 Year Old Girlfriend Has Baby Fever

It's Okay If You Don't Have Babe Fever!

A deep, sudden longing for babies is certainly real, merely it's not a prerequisite for having kids.

Just equally soon as they printing Salvage on their out-of-office responses this week, many Americans volition catch what, statistically speaking, Americans unremarkably catch during the cold winter months. No, hopefully not COVID-xix. I'm talking about baby fever!

The holidays are the high flavor for baby-making, which is why then many people are built-in between August and October, or about nine months from the week when anybody stops working and starts drinking hot alcohols. This phenomenon, which scientists call birth-rate seasonality, may have to do with ancient fetal-resource needs, sperm quality, or, this year, the fact that there is yet some other goddamn coronavirus variant afoot and only so many seasons of The Surface area.

Simply some people—research and, frankly, existent life shows—volition get pregnant this wintertime without getting baby fever, without fifty-fifty thinking about babies, and indeed without really meaning to at all. And I'm here to tell you that'southward besides totally normal and fine.

Being a woman of what obstetricians charmingly call "avant-garde maternal age," I have tried to discover the mysterious forcefulness that is baby fever, so far to no avail. At kickoff, I idea I'd become babe fever when I woke upwardly on the first day of my 35th year, my body suddenly deciding that I would enjoy changing diapers more watching Television receiver. That didn't occur, so instead I've spent the year waiting for it to seize me randomly, like a preteen X-Man expecting his powers to kick in whatever minute. When a baby smiles at me, I smile back, thinking perhaps he's a messenger from the Baby Realm. At Target, I walk past hand-size T-shirts that say milk monster, and I feel nothing.

Reading accounts of baby fever makes me feel like a bullheaded person subjected to long descriptions of colour. I observe posts like this, from an advice web log for moms, the least relatable affair I've e'er encountered: "I'd scroll upward with my dog and think, 'I wish I was holding someone circular and soft and stubby.' I'd watch Jason set the table for dinner and wonder what our babe would look like. The sight of our spare bedroom and empty back seat in our auto fabricated my chest tight, I couldn't hear about other people'southward pregnancies without trigger-happy up."

I began to think that, if you don't get infant fever, maybe that means you're not meant to have a baby. Something akin to "journalism fever" compelled me to movement across the land twice for this cursed profession. Surely a baby—just every bit grueling and economically disadvantageous, though arguably cuter—requires a like state of delirium. Correct? Wrong.

When I read a description of infant fever to Tanya Perez, a mother of two adult sons, she said, "That is wild that is actually how some people are motivated. I but discover it hard to believe." Perez always liked older kids, only she thought babies and toddlers were too needy and demanding. As a young wife, she loved her life with her husband, and she worried kids would put an cease to spontaneous date nights and weekend ski trips. But when she was 30, the couple moved to Virginia from California, and Perez missed her own mom dearly. "I only valued that adult parent-child human relationship then much," she told me. She assessed it rationally: What if she didn't like being a parent for the first 10 years, but then loved the adjacent 50? And so she went for it.

Having her first son surprised her. She and her husband didn't go on dates for a year, but she barely noticed. And then came non baby fever, just another cost-benefit analysis: It'd be overnice for her son to have a sibling. And then he got one. She still isn't particularly drawn to other people's babies, though. So hither we take a counterexample: Two babies, but no fever.

To be sure, babe fever is real. Both women and men get it, though women get it more oft and more strongly. The experience of babe fever varies from toying with the idea of having a child, to all of a sudden seeing babies everywhere, to "deep sorrow and acute longing," says Anna Rotkirch, a research professor at the Population Research Plant, in Finland, who has studied the phenomenon. Many people describe baby fever as hitting them unexpectedly, like a sudden downpour. A adult female in ane written report described it as "a huge longing, which starts from my womb and radiates to all parts of my body." Triggers seem to include inbound one's 20s, falling in love, seeing friends have babies, and having had i child already.

In 2011, the Kansas Country University psychologist Gary Brase and his married woman, Sandra, explored the phenomenon past request people, in part, "Practice y'all at times feel a bodily desire for the experience, sight, and odour of an infant next to you?" The Brases institute, mayhap intuitively, that people who get infant fever tend to react more than strongly to the pleasant things about babies (like their oddly exhilarant caput olfactory property), and less strongly to the unpleasant things about babies (like almost of their other smells). They besides don't tend to feel like having a child would seriously compromise their other goals. More surprisingly, the Brases found that for women, babe fever peaks in one'due south 20s and gradually declines with age. Meanwhile, immature men are less prone to baby fever, only their desire for babies grows more frequent every bit they historic period—such that in their 40s, men take, on boilerplate, more than baby fever than women do.

Just how many people get baby fever is harder to say. In ane of Rotkirch's Finnish studies, 44 per centum of men and 50 pct of women said they "have longed to have a infant" at least once, only men's baby fever was, again, less frequent and less severe. Men's baby fever was besides less probable to result in an bodily baby than women's was, suggesting that while a human being might phase a clever baby lobbying campaign, ultimately the woman's vote (and her uterus) is what actually matters.

Many women go mothers without e'er experiencing infant fever. In 2006, Rotkirch asked readers of the Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat to write to her virtually their experiences related to baby fever —vauvakuume in Finnish. She received 106 responses from women. In 12 of them, the woman said she had never felt infant fever, but she either has or wants children. In other research, Rotkirch found that 22 percentage of women never felt whatever "infant longing." And fifty-fifty amid those who did, she writes, "babe longing is not equivalent to having children—even among parents with 3 or more children, one in three men and one in 7 women report that they have never felt a strong longing to have a child." In other words, some women got pregnant and gave birth three different times without ever feeling a particularly strong desire to do either. Infant fever was a fairly of import reason these Finnish couples had children, only so was simply making a sibling for an existing kid. "'Infant fever' is not a universal role of our emotional repertoire, and one should not expect to feel it before having children," Rotkirch said via email. "There is nothing 'wrong' in not having baby fever and deciding to have a child, or vice versa."

Some people desire to be parents, for instance, only they don't want to physically carry a child. Cathy Resmer, the deputy publisher of the Vermont newspaper 7 Days, wanted to raise kids, merely had no want to be pregnant and give birth. She was thrilled when she met her wife, who did. Resmer says the nascence of her son and daughter fabricated her appreciate babies more than than she did before, but the baby years weren't her favorite time; the teenage years are. "I never had infant fever, but I might have had teenager fever?" she says. "As much fun as they were to watch dorsum and so, they're so much more than fun to interact with at present."

An underexamined and surprisingly common feeling in the atomic number 82-up to childbearing is ambivalence. When asked to think dorsum on how they felt about their recent pregnancy, well-nigh 15 percent of American mothers say they "weren't sure what they wanted," as opposed to wanting to exist pregnant correct then, at a unlike time, or never. In a series of three surveys conducted a decade agone, ix percent of women consistently said they were uncertain near having children or most having any more children, and women over xxx were more likely to experience this way. Of course, more women effectually the world—specially those who are highly educated and career-oriented—are remaining kid-complimentary by selection. Still, many women who consider childlessness go on to become mothers.

"Pregnancy intentions are really nuanced and complex, and they're not fixed," says Laura Lindberg, the master inquiry scientist at the Guttmacher Institute, which supports ballgame rights. "You don't wake up the day you get your period and make up one's mind, 'Aha, I am a woman now and here are my fertility plans.'" The skimpiness of the American social rubber internet can add a ruthless practicality to pregnancy decisions: Many women say they want to get significant "at some point," but not with their current partner, or non until they make more money, or non until they've bought a house. Baby fever might not pitter-patter in before a solid credit score does. Meanwhile, for depression-income women, an IUD might be more affordable than a baby, so whatsoever want for a family might be shelved involuntarily until afterward.

My friend Caitlin, whom I've identified by her first name so she could be frank about her reproductive decisions, is one of those adults who e'er idea they didn't know how to talk to kids. She didn't accept a positive or negative view of children; she just thought they were a different species. She never had babe fever, including the day she found out she was pregnant. She was broke, and she considered an ballgame. So she idea, "If nosotros were going to have one, and so, you know, why non now?" E'er since, she's been happy with her decision; her son has fabricated her a better person, she says. Merely the fashion things are going in Texas, where she lives, parenthood might not be a choice for much longer. Women who get meaning accidentally might have to give birth, baby fever or non.

Lots of people are in a similar place, feeling like they don't want to accept a baby, but also don't not desire to have i. People'due south actions and feelings don't ever line up: In research, many women who weren't using contraception and got pregnant said they were unhappy nigh information technology, but similarly high percentages of women who were using contraception and got pregnant anyway said they were happy virtually information technology. "In that location's this term between planned and unplanned," Heather Rackin, a sociologist at Louisiana State Academy, told me. "Yous're not trying to have a kid. But you lot're likewise not not trying." Some people don't seem to realize that their actions are pointing in the "baby" management. They volition go off birth command and commencement having unprotected sexual practice, "but if you ask people at these stages, 'Are you trying to have a baby?' they'll say no," says Jacky Boivin, a health-psychology professor at Cardiff University.

In fact, some researchers think infant fever is a reaction to infertility struggles, not a ubiquitous maternal urge. Many women never experience babe fever, considering they successfully get pregnant within a few months of going off contraception. Only if months go by without a pregnancy, "these kinds of yearnings are triggered considering it'southward something that you actually want, and you accept a blocked parenthood goal," Boivin says. The "broodiness"—every bit baby fever is chosen in the U.K.— "is not the cause of you lot wanting to have children. It's a event of you wanting to have children and not being able to take them."

Rackin suggested that binary notions of motherhood—either you want information technology or don't; yous either take babe fever or not—originated back when most women were expected to accept kids. Just now society has ratcheted up what it takes to be considered a "qualified" parent. The norms of upper-middle-class life pressure people to have an educational activity, a task, a auto, a house, and a stable spouse before they even consider parenthood. "It's really difficult to check all those boxes off and exist able to say, 'Now I'm going to try to accept a babe,'" Rackin said. It's less romantic and more than daunting to plow 36, laissez passer the bar exam, and get your IUD removed than it was to get pregnant on your honeymoon as a 21-twelvemonth-old in 1957. Avoiding planning too difficult or also purposefully is a way, for some people, to "non accept to feel bad about not checking all those boxes earlier having a child," Rackin said.

In that way, baby fever tin can feel similar another societal box to check, another affair about which to think, I don't accept it, so I must not be ready. But, and I say this to my fellow anxious perfectionists: The homo race would disappear if nobody got pregnant without first being struck past a special thunderbolt from God. I am not telling you to have unprotected sex this holiday season; I am merely telling yous, if such metrics are important to yous, that lots of people are, and that but some of them accept baby fever.

My 20 Year Old Girlfriend Has Baby Fever

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2021/12/how-common-baby-fever/621083/